Traces of Spaces

TRACING THE TRACES. TRACES OF SPACES.

A project for several mapping stations in and outside.

The artist Nikolaus Gansterer has a deep interest in the links between drawing, thinking and action. While having had an ongoing practice of mappings and diagrams, in his recent project he is focussing on the exploration of expanded drawing.

Is it possible to let the inherent dynamics of space be recorded, mapped and drawn by themselves? Therefore, dynamic things in public space such as trees, wind, insects, etc., are tested to become drawing tools, capturing unique described movements. Thus, for example, a writing tool suspended inside hardware inscribes on a paper the wave movement of a canal, drawing instruments held on stretched ropes are pressed onto paper by birds sitting on the ropes,

papers attached to street cars brush through the city or even plain papers get buried in the park becoming a test field for microbial activities: All of these experiments offering a very specific insight on the otherwise invisible traces of the urban spaces. Each of the drawing stations distributed in the city is its own performative spot at which the observer can follow the process.

All the resulting material are put together into a growing archive and can be seen in the context of a presentation and a series of performative installations at the Art Centre Vooruit during the festival “The game is up” in March 2011. Then the artist is also planning to compile his findings in a small publication.

Concept and idea: Nikolaus Gansterer

Thanks to Kurt van Houtte for his technical advise.

Technique: various drawings

Dimensions: variable

– 2010/11, timelab, Gent and "The game is up", Vooruit, Gent/ Belgium. Curated by Eva de Groote and Tom Bonte.

– 2011 Entartainer, Parkfair, Vienna, Austria.

– 2011 Convergence in Probability, Galerie Stadtpark, Krems, Austria

– 2011 The Borders of Drawing, Weisses Haus, Vienna, Austria.

Publications:

– Convergence in Probability, Nikolaus Gansterer, Brigitte Mahlknecht, David Komary (Ed.), exhibition catalogue, Galerie Stadtpark, Krems, 2011.

– "The borders of drawing", Artycok-TV, 8.4.2011

– "Gruppenausstellung The Borders of Drawing", Die Wiener Zeitung Online (15.2.2011)

– "Nikolaus Gansterer im Interview", mit Eike Johannes Lucas, in: iGNANT.de, 13.5.2011.

Relevant texts:

Traces of the other (and of interventions, modes of being, and interpretations)

On Traces of Spaces by Nikolaus Gansterer

Text: Pieter van Bogaert

Nikolaus Gansterer usually makes his own drawings, but in 'Traces of Spaces' he delegates the labor of drafting to the other. That is: not to 'an' other, but to 'the other', the ulterior—the draftsmen here are the wind, water, plant life, and passersby of all sorts. An exhibition at the Vooruit Arts Centre brings the disparate elements of his project together: installations show things at work; an archive displays the artist’s harvest.

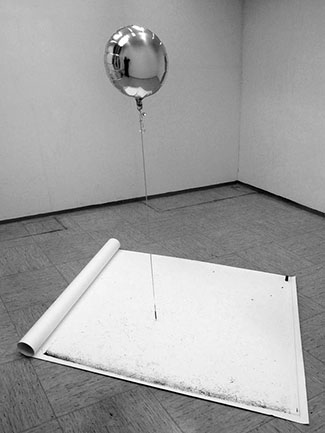

Gansterer and I meet over drinks at the Vooruit café. In front of us sits a pedestal, about the size of a coffee table. Three balloons hover above it. Attached to each balloon is a pen, which moves across the surface of a sheet of paper guided by the balloons. On the paper, dots record where the pen halted, lines where it moved between resting points. Outside, plastic boxes bob in the water of the Leie river, which flows behind the Vooruit. In each box too is a pen, which moves in sync with the lapping waves of the water and leaves its marks on a piece of paper attached to the ceiling of the box. In one of the turrets of the Vooruit, a pen dangles on a wire that branches off into four directions. Each wire runs out of one of the windows to a balloon drifting in the wind. From inside the Vooruit’s turret you can see the Ghent Belfry, where Gansterer attached a small plastic box containing pen and paper to one of the big bells. Every quarter of an hour the box registers the movements in the tower. And not too far from there, in the botanical garden, a pen traces the growth of a bamboo shoot.

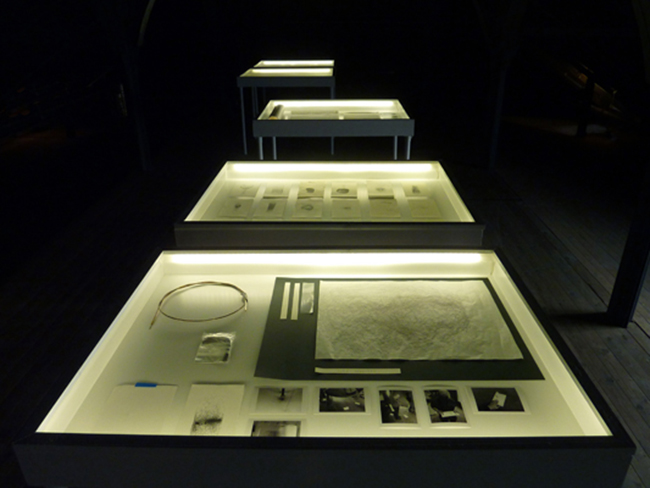

Every day Gansterer treks to the installations to harvest their yield. Those drawings are then added to an archive nestled in the attic of the Vooruit. There they are lain horizontally inside tables topped with sheets of glass that open easily, so that the artist can add more on a regular basis. Returning visitors, then, can track the archive’s growth. But what is augured in these movements? What meanings circumscribed on these sheets?

Traces. Foremost, these drawings show us traces. And each trace always carries a meaning. It is about what we are looking for but reluctantly leave behind. Or what we leave behind but are loath to find. What we organize yet still try to avoid. Traces incite fascination as much as irritation.

We clean because we don’t like trash. We wash our hands because we value hygiene. We’re mindful of the environment because we worry about melting polar caps. We select private browsing for things no one else needs to know. Doggie poop bags, trash cans, air fresheners, anti-aging crèmes, toilets: all traces of our quest for a traceless existence.

We erase our traces, but also organize them. Cars on the road, cyclists in the bike lane, pedestrians on the pavement, boats on the water, and streetcars on their tracks. We register earthquakes, forecast the weather, and measure air quality. We write letters, arrange an inheritance, make art. All of these are traces of mediation. Of passage. Traces of spaces shared.

It is these shared spaces to which Traces of Spaces speaks. This work shows us traces of an artist. Traces of interventions. Each drawing is marked by presences, by modes of being that are at the same time also interventions. Ultimately what we see are traces of passersby, of things that have passed: interpretations as much as they are interventions and modes of being.

Spaces. 'Traces of Spaces' deals with spaces of latent potential, performative spaces. Towers to be looked at. Rivers to be followed. A live-and-let-live garden. A café that generates relations and interaction... The work is about spaces in which to dwell. An archive—this exhibition—in which all of these spaces coalesce; a residency—Timelab—from which they depart.

Every space marks a stand: a moment of standing still, of reflection, of planning, of plotting course, and of letting go. Because even though you can stake a space with an intervention, a mode of being, a presence, an interpretation, time and again that space needs to be given over again... to space. You have to let go of it and return to it the possibility of its own interventions, modes of being, and interpretations—to let a space live.

Drawing. Gansterer allows the space to draw. Yet, the artist is an experienced draftsman. He calls drawing a “medium of high immediacy.” What does that mean? That it takes little or no tools or media? Why then these elaborate installations? That it manifests itself fast or immediately? Then why is it these drawings take twelve hours or more to complete? Is drawing perhaps self-effacing, effecting a near-disappearance of the medium in its making? I think not.

Each of these installations, on the contrary, renders the medium highly visible. Perhaps it is more apt to speak of hypermediacy, of ultra-mediation. The box floating on the water in which a pen registers its movements on a sheet of paper; the wires fanning out in four directions but meeting in a pen; the pen attached to a shoot of bamboo; the pens linked to balloons that register the slight quivers of air provoked by passersby: all of these are highly visible media that take over the role of the artist. That too is a way of letting go. These installations signal humbleness and allow the artist to move away from the instrument(al).

The artist creates (intervention) a relationship (mode of being) and in return begets a drawing (an interpretation). And it is exactly here that the performative aspect of these drawings, of the installation, and of the archive can be located: object becomes action.

Elements. Gansterer is a collector of traces, a harvester of drawings. He combines the methodology of the archivist with that of a gardener: collecting, pruning, and maintaining, but also forecasting and taking advantage of the unpredictability of the elements. He seeks them out: the air currents around the turrets of the Vooruit and the Ghent Belfry, the water of the Leie river, microorganisms in the soil. These are some of his basic tools: pen and paper, of course, but equally likely a piano wire, a string of hair, a feather, a thin layer of chalk, a balloon or a plastic bag, some earth or a bit of sugar.

High-tech this is decidedly not. No viewfinders, lenses, clichés or reference images. We’re dealing with the artist as medium, as machine, as routine. This is about extra-human drawings. That doesn’t necessarily mean objective, nor does it mean mechanical. Perhaps organic is an appropriate term. And subjective, but paradoxically seen from the perspective of the object.

Measuring. Gansterer not only inhabits the roles of gardener and archivist, he is also an accountant, an economist concerned with the housekeeping of things. His work consists of registering dynamics and taking measure. It is a form of mapping, a cartography of movement.

Cartography surfaces in Gansterer’s ongoing project Drawing a Hypothesis in the form of diagrams, drawings that often feature the results of measurements. By copying the diagrams and stripping them of explanatory text, he passes the labor of interpretation from the scientist to the viewer. It seems like the opposite strategy of Traces of Spaces. Where the latter aims to register movement and thus capture it, the diagrams intend to bring these drawings back to life by interpreting them; each interpretation is a translation that produces a survival. But of course that is also the task at hand in Traces of Spaces. The work doesn’t end with intervention, nor with presenting a mode of being. It also demands an interpretation which—and we’ve noted this already—is always both intervention and mode of being.

Gansterer follows in the footsteps of historical scientists. Someone like the Bengali natural scientist and biologist Jagadish Chandra Bose, for instance, who at the start of the 20th century invented the crescograph, a device for measuring the growth of plants. The great difference with Bose’s work and that of other scientists who employed seismographs, rotameters, or manometers, is that Traces of Spaces isn’t concerned with precision as much as with feeling. This is not a scientific endeavor but an esthetic one. The analog is of crucial importance here, as is scale. Because size does matter: more intimate formats are more effective. They make for higher concentrations.

Apparatus. All these measurements result from the deployment of an apparatus, and the artist designs a new one for each situation. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben recently published a small booklet bearing the grand title Che cos’è un dispositivo? (or What Is an Apparatus?). An apparatus, so we learn, comprises everything that can record, direct, define, shape, control, and secure the actions, opinions, discourses, and behaviors of living beings.

The apparatus is a device, a compelling possibility. It is a means, a median, a mediator. It is that which turns being into becoming: a process, a differentiating, a becoming-other. More than an instrument, it is in and of itself a force, a generator, a mediator, a medium. It produces users. The fundamentally generative, creative power of the apparatus, its capacity for transformation, is what makes us part of those apparatuses, what compels us to act through them. The apparatus (dispositivo) dis-positions: it places and displaces the viewer into the work.

However, where in Agamben’s text the apparatus appears as a disciplinary device that controls and subjectivizes—think of a prison, a language, a cell phone—Gansterer’s oeuvre suggests the opposite. The ways in which the artist renounces control of his pens and constructions effect a liberation, not a disciplining. It is a way of letting go, not of control. It objectivizes rather than subjectivizes. The result is a displacement, a dispositioning in the purest sense of the word. It is an attempt to inhabit the other, or otherness. His work produces a constant becoming: becoming plant, wind, water, bell, microorganism. It is an accumulation of processes in which each interpretation is always already a mode of being, and each mode of being an intervention.

Convergence in Probability (Drawing and Processes of Drawing), (2011)

Excerpt of the opening speech by Natascha Gruver at the exhibition “Convergence in Probability,” Galerie Stadtpark, Krems ___________________ download text (English)

Traces of movement—traces of memory—traces of thoughts:

On three tables you can see works from Nikolaus Gansterer’s “Traces of Spaces” project created in 2010/2011 during a Residency in Belgium (Gent).

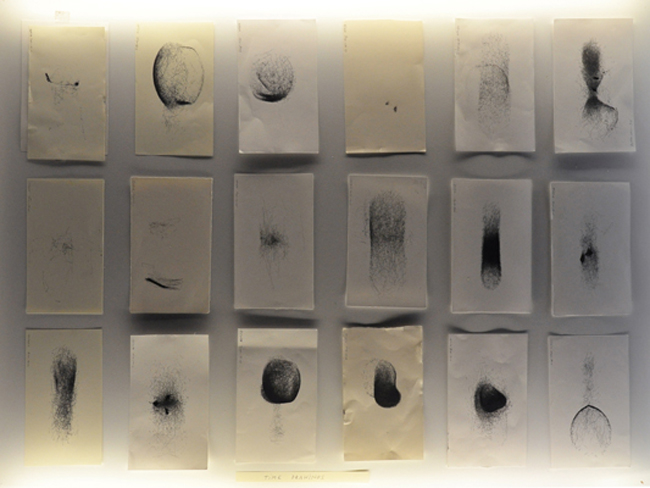

The theme in “Traces of Spaces” is recording the self, an automatic drawing or automatic drawing, where the artist does not draw himself, but creates a situation in which recordings can take place autopoietically, self-generating. For that, Gansterer constructed analogue “recording machines,” (for example, a box with a pen mounted in it) that were set up at different sites, and which, once set in motion, seismographically recorded the surroundings. The tables show the drawings created by this recording system.

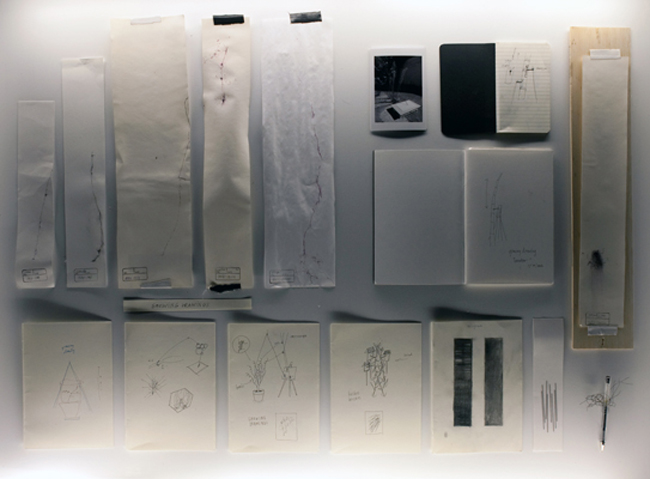

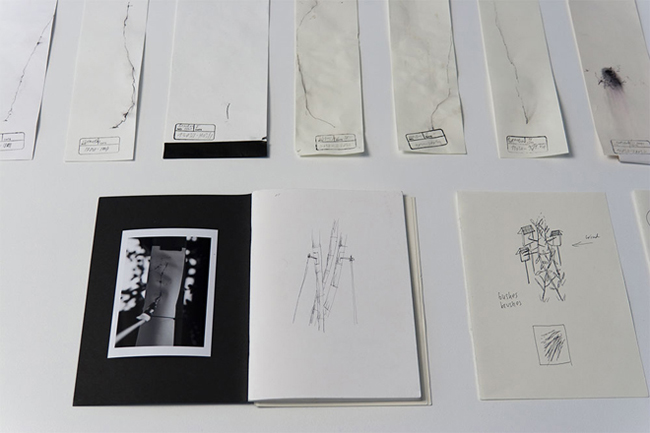

Physical processes, such as oscillations and vibrations (e.g., from concrete, guard rails, train tracks) inscribe themselves onto paper. The pen mounted in the box becomes a seismograph of movement, of physical processes. A different construction records biological processes, such as the growth of a plant. What you see on table three are the traces made by a pen hung on a bamboo plant that was connected to a piece of paper.

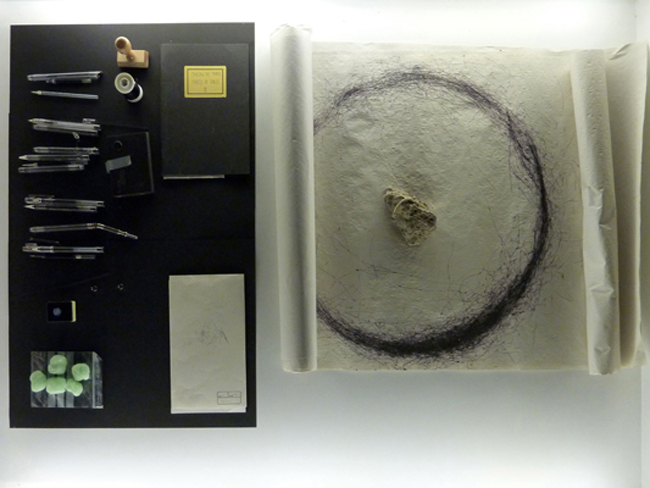

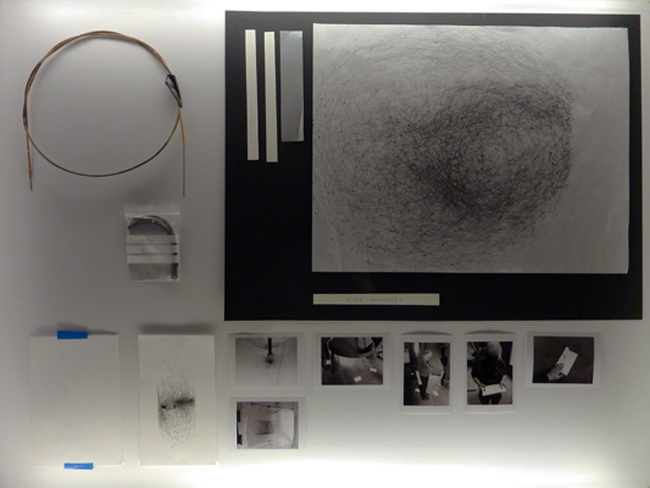

The first table refers to natural history showcases in museums and shows the working instruments, writing utensils and rolls of thread that were used in the analog recording machines.

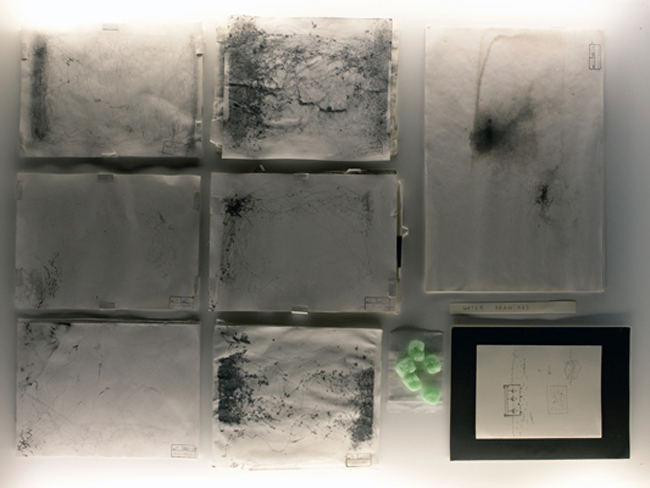

The second table shows the recordings (traces) of a recording machine

(box with pen), which reacts to vibrations and records them in analogue form. The box was set up in different public sites: on a highway, on a church clock tower, and was also worn by the artist himself, on his body.

The concept of “Growing Drawings”: the seismographic recordings grow, they are generated within the certain time frame that the box, the “recording machine,” is set up, which can encompass hours, or even days, weeks, or months (in the case of the plant’s growth).

The third table shows the traces of a biological process, the growth of a plant. Something living begins to record itself, and leave behind traces of its growth. In this case it was a bamboo bush in the Palmenhaus. The drawing apparatus, the recording machine, is a pen mounted on a bamboo leaf, and connected with a piece of paper that is mounted in a fixed position. The apparatus is a copy that refers to the Crescograph, which was originally invented and built by Indian-British scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose. With the Crescograph, growth movements are engraved on a smoked glass plate.

Gansterer stages a seemingly scientific collection of “natural” recordings and artifacts. The recordings seem purely perceptive, produced without the help of a subject. The drawing systems generate traces and appear to depict reality, however: the selection and arrangement of the recordings on the table is clearly recognizable as a scientific staging, as “staging of science (scientific character).” What is important to see here is the context of machine, site, and drawing. I thus find the sketchbook on table three quite stunning and appropriate where the operational mode of the crescrographic drawing apparatus can be seen as a type of technical sketch.

The question of what one wants to record and how one generates a situation that makes that possible, transcends the drawing as medium. Gansterer thereby shifts this question from the level of pure data collection, of apparently objective scientific observation to the meta-level of scientific staging. What can also be said of Gansterer’s works and working methods as a whole, is that he works via project cycles based on particular questions. A particular aesthetic develops from that. Rather than pursuing a type of drawing “monogamously,” various processes, methods, and aesthetics emerge based on the particular, project-specific line of questioning. Gansterer’s theme is drawing, as such, drawing also as performance, as performative process.

German version:

Convergence in Probability (Zeichnen und Prozesse des Zeichnens), (2011)

Remarks on the work "Traces of Spaces by Nikolaus Gansterer

Excerpt of the opening speech by Natascha Gruver at the exhibition "Convergence in Probability", Galerie Stadtpark, Krems. ________>>>_Download full length text (German)

Bewegungsspuren – Erinnerungsspuren – Gedankenspuren:

An drei Tischen sehen Sie Arbeiten aus dem Projekt Traces of Spaces von Nikolaus Gansterer, entstanden 2010/2011, während einer Residency in Belgien, genauer in Gent.

Das Thema in Traces of Spaces ist Selbstaufzeichnung, automatische Zeichnung, bzw. automatisches Zeichnen, wo der Künstler also nicht selbst zeichnet, sondern eine Situation schafft, in der Aufzeichnungen autopoetisch, selbstgenerierend, stattfinden können. Dazu konstruierte Gansterer analoge ‚Aufzeichnungsmaschinen‘, (z.B. Box mit montiertem Stift darin) welche an verschiedenen Orten aufgestellt wurden, und die, einmal in Gang gesetzt, seismographisch die Umgebung aufzeichneten. Die Tische zeigen die von diesen aufzeichnenden Systemen hergestellten Zeichnungen.

Physikalische Prozesse, wie Schwingungen und Vibrationen, (z.B. von Beton, Leitplanken, Eisenbahnschienen) schreiben sich auf Papier selbst ein. Der in der Box montierte Stift wird zum Seismographen von Bewegung, von physikalischen Prozessen. Eine andere Konstruktion zeichnet biologische Prozesse auf, wie das Wachstum einer Pflanze. Was Sie an Tisch Drei sehen, sind die Spuren eines an einer Bambuspflanze aufgehängten Stiftes, der mit einem Blatt Papier verbunden war.

Der Erste Tisch zeigt, in Anlehnung an naturhistorische, museale Vitrinen, die Arbeitsgeräte, Schreibgeräte und Fadenspulen, die in den analogen Aufzeichnungs-maschinen verwendet wurden.

Der Zweite Tisch zeigt die Aufzeichnungen (Spuren) von einer Aufzeichnungsmaschine (Box mit Stift) die auf Vibrationen reagiert und diese analog aufzeichnet. Die Box wurde an verschiedenen öffentlichen Orten aufgestellt: an einer Autobahn, auf einer Kirchturmglocke, und auch vom Künstler selbst am Körper getragen.

Das Konzept des Growing Drawings: die seismographischen Aufzeichnungen wachsen, sie entstehen innerhalb eines bestimmten Zeitraumes, über den die Box, die „Aufzeichnungsmaschine“ aufgestellt ist und der sich über Stunden, aber auch über Tage, Wochen, sogar über Monate (im Fall des Pflanzenwachstums) erstrecken kann.

Der Dritte Tisch zeigt die Spuren eines biologischen Prozesses, das Wachstum einer Pflanze. Etwas Lebendiges beginnt sich selbst auf zu zeichnen, und Spuren ihres Wachstums zu hinterlassen, in dem Fall war es ein Bambusstrauch im Palmenhaus. Der Zeichenapparat, die Aufzeichnungsmaschine, ein Stift, an einem Bambusblatt montiert, und mit einem fix montierten Blatt Papier verbunden. Die Apparatur ist in Anlehnung an den Crescographen nachgebaut, der ursprünglich vom indisch-britischen Wissen-schafter Jagadish Chandra Bose erfunden und gebaut worden ist. Beim Crescographen werden Wachstumsbewegungen auf russgeschwärzte Glasplatten eingraviert.

Gansterer inszeniert eine wissenschaftlich anmutende Sammlung von ‚natürlichen’ Aufzeichnungen und Artefakten. Die Aufzeichnungen scheinen rein perzeptiv, ohne zutun eines Subjekts entstanden zu sein. Die graphischen Systeme erzeugen Spuren und scheinen die Wirklichkeit abzubilden, jedoch: die Selektion und Anordnung der Aufzeichnungen auf den Tischen ist deutlich als wissenschaftliche Inszenierung, als „Inszenierung von Wissenschaft(lichkeit)“ erkennbar. Wichtig ist hier zu sehen: der Zusammenhang Maschine, Ort und Zeichnung. Sehr schön und passend finde ich daher auch das Skizzenbuch an Tisch Drei, wo, als Art technische Skizzen, die Funktionsweise des crescoraphischen Zeichenapparats zu sehen ist.

Die Frage: was will man aufzeichnen, und wie generiert man eine Situation, die das ermöglicht, geht über das Medium des Zeichnens hinaus. Gansterer verschiebt damit die Frage von der Ebene des reinen Datensammelns, von scheinbar objektiver wissenschaftlicher Beobachtung auf die Meta-Ebene der wissenschaftlichen Inszenierung. Insgesamt ist zu den Arbeiten und Arbeitsweisen von Gansterer noch zu sagen: er arbeitet über Projektzyklen, anhand bestimmter Fragestellungen. Daraus entwickelt sich eine bestimmte Ästhetik. Es wird nicht “monogam” nur eine Art des Zeichnens verfolgt, sondern verschiedene Verfahren, Methoden und Ästhetiken emergieren anhand der jeweiligen, projektspezifischen Fragestellung. Gansterers Thema ist das Zeichnen als solches, Zeichnen auch als Performance, als performativer Prozess. (for full length text please download the pdf)

Interview in Radio Orange "PhiloBrocken" with Natascha Gruver (2012) >>>_Listen to the file